2019-12-09

Series "Artist Entrepreneurs"

Authors

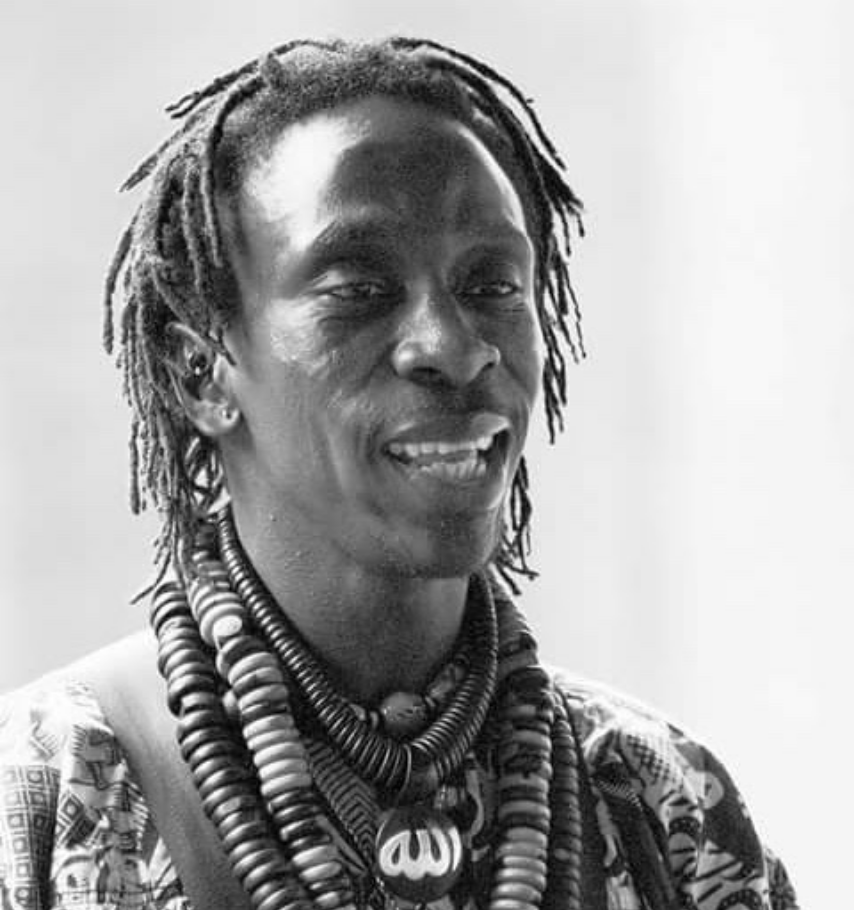

Oumar Sagna

is a prolific musician, dancer, arts researcher and educator from Senegal. He studied the rhythms and performance traditions of his homeland and provides traditional rhythm sections across the world. Oumar founded and manages his own successful company Mandinka Roots, providing tuition and performance development across a range of community and private sector organisations, in schools and during corporate events, and preserving the highest quality West African arts in the Diaspora.

Polly Crockett

started her career in the arts over 25 years ago. She founded and directed a dance company which still thrives to this day and has created several screen dance projects. She now focuses more on the business and management of the arts industry, specialising in cultural partnerships, organisational development and consultation. She is especially drawn to activities and projects that grow in response to the surrounding social environment and believes that one's focus should never stray too far away from the grass roots.

Promoting the meaning of art to Western societies

Filling a gap as a self-employed international artist and arts educator

For many artists, dealing with the artistic traditions of their home country is a form of identity building and affirmation. Therefore, they can be perfect trainers for such processes. By seeing gaps in the European education system, Oumar Sagna, a musician and dancer from West Africa, is able to stand on his own two feet as a musician and dancer. He uses his cultural traditions to enrich other cultures by teaching them to children and communities, especially in the UK.

Series "Artist Entrepreneurs"

In this series, Managing Artists, Polly Crockett talks with independent creators from around the world, who have found ways to manage their own business, whilst succeeding in being artists. Conversations have been turned into written portraits providing the opportunity to read about and appreciate the working life and learned skills that have evolved for each individual.

Having been brought up in Senegal in the city of Dakar, Oumar was surrounded by arts education, "…in Senegal you have music around you 365 days of the year”. At the age of twelve he started dancing and playing instruments and over the years found himself playing with large groups in various venues. These opportunities provided continuous inspiration since audiences would actively take pride in appreciating music that was gifted to them and looked upon musicians as they might famous celebrities. "Life was a party. Ten musicians and ten dancers would perform to crowds of people. We would practice every day all day, non-stop. When you open the door in the music world in Senegal, you find hundreds of other doors. I trained in fire breathing, walking on stilts, playing drums, making instruments, performing live, for radio, for TV, the list was endless.”

Oumar was living a life that was making him happy, but it was not making him money. He had a family to support and was struggling financially. He worked hard to become more skilled, learning different styles of dance and the piano, perfecting fire breathing, and eventually the word spread that he was a performer that businesses and producers could call upon. "I had started to become more in charge of my life and my business started to grow.” At this point, though, Oumar was still needing to do a variety of work in order to support his art.

Arts Education in the UK is Limited Compared to Senegal

It was a UK contact that changed his world. In 2003, Oumar was involved in a drumming group exchange. A successful audition gave him a ticket to visit the UK and he quickly understood the opportunities that were open to him now. "Schools in the UK don’t offer arts education like they do in Senegal. It doesn’t seem to be part of their culture. Everything that is regularly offered to youngsters has to be business led. In Senegal we don’t think about business first, arts are part of how we talk, how we communicate, and how we go from day to day.”

This major difference in culture became of interest to Oumar. Within it he found a solution that could give him business opportunities and scratch the surface of providing youngsters in the UK with an understanding of African education through music, dance and history. "The UK are giving lip-service to the arts and black history, but there is never a depth to their learning, everything is rushed.” But the idea that the education system acknowledges the need for a better arts education is enough for Oumar, his business is busy. "I’m in London on Monday, Northampton on Tuesday, going to Wigan next week” and the list goes on. "I can be an artist and I can earn my living, because I’m not from here.”

"My strength is my will to never stop learning.”

But Oumar is very clear about the importance of balancing both an arts education and an academic education. "I have friends in Senegal who are talented in their art, but who cannot read or write. I have a university degree and I thank my father for that. He made sure I kept studying. Without my education I would not have the confidence and the ability to be able to manage my work. You have to be prepared mentally to accept that energy is needed to build a business including marketing, advertising programming.”

It is likely that Oumar’s upbringing and surroundings have provided him with the principles he has and because of which he will never put one hundred percent of his effort in to one area. "I believe I can always learn. In music you can swim as far as you want, but there will always be hundreds of miles ahead of you. I am always prepared that I might need to do other work to earn money, and that is fine, it is part of life and part of living. I thrive on challenges. After all, I’ve had to learn English and how to survive in another country. I will never be complacent.”

Sub-Cultures are as important to understand as a national culture.

And, whilst Oumar prepares thirty drums for a class of thirty children who he is teaching a few hundred miles away, he talks to me about his organisation skills and the need to ensure them, and says something extraordinarily poignant: This performer, who has identified culture gaps that he is helping to fill, realised that pockets of sub-cultures arise, and the needs of youngsters in a country as small as the UK vary from area to area. "Behaviours of youngsters are different whereever you go. Attitudes change and desires are different.” This acknowledgement that ‘one size does not fit all’ explains how he runs his business. He observes his surrounding all the time and has the ability to provide and share his artistic knowledge in a way that is needed, so that those he works for always want more.

Knowledge exchange keeps us globally connected.

As we talk, we both realise the same potential issues that could arise. Whilst knowledge exchange is key to our ability to understand and feel globally connected, the constant threat to working internationally looms for people such as Oumar. "If we didn’t have the ability to cross cultures and move countries we would all be stuffed.” The differences in economy, development and cultural education across the world is certainly a fact of life. This means that a performer like Oumar can thrive whilst he boosts the moral, experiences and opportunities of others. However, if these possibilities are squeezed out entirely, where would we all be and what would we have left?

There are no comments for this content yet.