2018-12-10

Authors

Stefan Rosu

works in the music business for more than 25 years. He had leading positions, e.g. at the Schleswig Holstein Festival and the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg. Since 2013 he serves as the South Netherlands Philharmonics first director general and artistic director. Rosu holds a PhD in philosophy and teaches orchestra management in Frankfurt/ Main.

Change in orchestras

The Maastricht Centre for the Innovation of Classical Music

Leading an institution in a period of change is one of the toughest challenges in cultural management today. As director of the philharmonie zuidnederland (South Netherlands Philharmonic), Stefan Rosu developed the idea of an independent scientific centre on Classical Music to conduct research on orchestras and advise them regarding innovation and renewal.

A symphony orchestra cannot re-invent itself on its own

In 2015, the philharmonie zuidnederland had just put itself on the artistic map again after a merger. It was presenting a large variety of activities for different target-groups, including the innovative series “spicy-classics”. The orchestra followed the roadmap of the Seven Factors of Success, determined by the orchestra itself. Deep inside, however, I felt that this orchestra had to go even further to firmly establish itself. One of the aspects I considered key was its ability to embrace and carry out change.

My approach as a leader to bring this ambition to life started from the understanding that the input for change could not only come from the players and members of staff – precisely because an orchestra’s artistic quality on stage is depending on a firm set of traditional internal values and workethics. We needed help. I therefore looked for ways to get additional input from outside and implement it in a way that the members of the orchestra (players and staff) would eventually be ready to embrace change and would start to move in new directions on their own conviction.

The Maastricht Centre for the Innovation of Classical Music

And suddenly the idea struck me: What if the orchestra would establish a centre in which scientists would look through the lenses of their disciplines at the phenomenon of orchestras and would suggest adaptions for renewal using their respective theories of innovation and modernization? And what if my orchestra would be involved in that process? In 2016 I approached the University of Maastricht with that unique proposal. The university was enthusiastic and we developed the idea further until the Centre became operational on September 1st, 2018 as the Maastricht Centre for the Innovation of Classical Music (MCICM).

Together we defined the Centre’s main research lines: Orchestrating social relevance, modernizing cultural participation and adapting sounding heritage. The MCICM will also collect and disseminates knowledge and information about classical music cultures. It does so by making up an inventory of relevant academic research as well as relevant practical experiments with new concert formats. This inventory will have the form of an international database for innovative initiatives and an international network of partner institutes.

We raised a budget of roughly 2 million Euros for the first six years of the MCICM’s existence. Through an international search procedure, Dr. Peter Peters was chosen to become the first professor for Innovation of Classical Music to lead a team of seven scientists with different fields of expertise. The intention is to build a knowledge centre and source for interdisciplinary research in which scientist and musicians work together. A laboratory for experiments and practical input for the classical music sector. The philharmonie zuidnederland is co-founder and co-financier of that joint venture. It also serves as the MCICM’s main testing facility.

Getting internal support

Parallel to the process of developing the MCICM with the university from scratch, I started to shape the orchestra’s business plan for the period 2017 to 2020. With the its commissions, boards and individuals I focussed the discussion on basically two general questions, one of them being: “Should we invest more funds in innovation and renewal?” And as a majority of the orchestra responded positively, the Centre became part of the orchestra’s own business-plan with a financial investment of EUR 250.000 Euro into the MCICM. Additionally, I pencilled time-resources and extra budget for the orchestra to play its part as testing facility. What I found very promising through the process of development was the fact that the player’s representatives kept supporting the idea even if it meant to have fewer budget available for permanent players or better salaries.

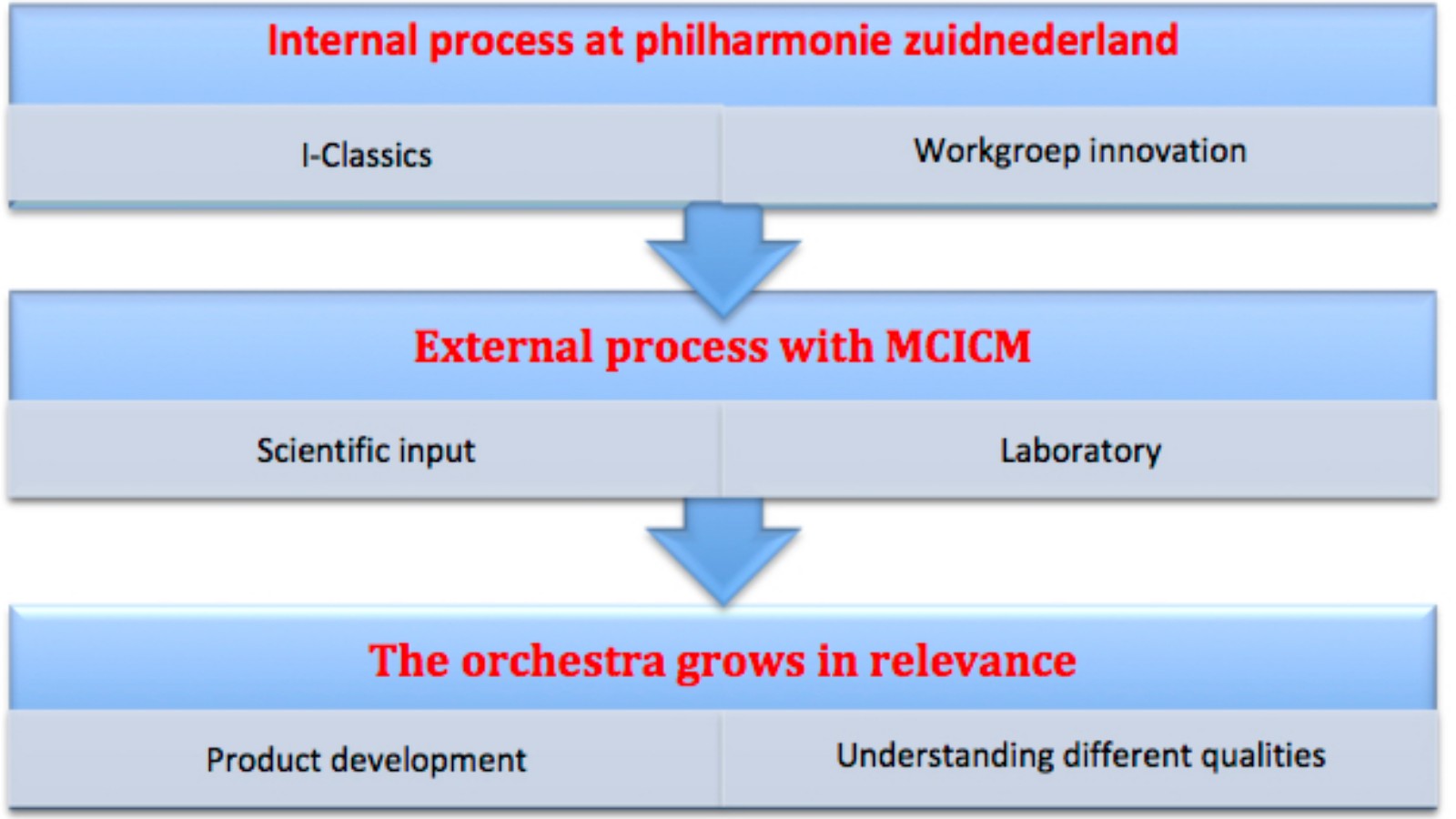

The link between orchestra and MCICM

The next step to support change was the installation of a “workgroup innovation” within the orchestra. It shall serve as an important link between the orchestra and the MCICM as well as a general internal sounding board for renewal. This group of eight consists of players and staff-members of different age, sex and diverse backgrounds. It receives a budget to check out projects and initiatives from other parties that seem interesting to them. The task of this workgroup is to advise me on all matters concerning innovation and renewal. Also will one or several members of the group accompany innovative projects while they are developed and realised by the orchestra.

The quality issue – a first result of a workshop

A first practical example for what kind of insights the co-operation between the orchestra and science can lead to was achieved before the MCICM even started its official activities: Prof. Ruth Benschop, an anthropologist attached to the MCICM, lead a workshop during the philharmonic’s members of the orchestra (players and staff) yearly meeting in summer 2017. She asked everyone to write down important moments in his or her career within the orchestra. Veerle Spronck, another researcher at the MCICM, analysed the outcome and came to a fascinating conclusion: Within the philharmonie zuidnederland there were two different perceptions about quality. One was the traditional perception of the perfection of the delivery and performance of a musical work in public. To achieve that quality aspects like “a good conductor”, “a good hall” or “I slept well today” were considered important. The second quality was identified as the orchestra’s educational activities, mainly for children and often in small ensembles. Here the musicians saw themselves in the role of the owner of a cultural achievement and measured the quality in how the musicians managed to connect to the children rather than perfect delivery. Very surprisingly to us all, both varieties of quality were seen as equally important. And Veerle wrote that it would be a great next step if “the orchestra would find ways to transfer this concept to the concert-hall”.

Conclusion

From my perception there are two crucial ingredients to achieve change within an orchestra: First of all, the leadership has to be an active part of and encourage a change process. Second, the process has to be a shared one. Musicians and staff have to have a very strong influence on the decision making processes. The establishing of the MCICM and how issues of change were discussed and included during this process are a good example of how to walk the path of change together within the institution. For philharmonie zuidnederland the existence of the MCICM will provide extra input and enlarges the chance that the orchestra will follow new ways to make classical music relevant to a broad public in the future.

There are no comments for this content yet.

similar content